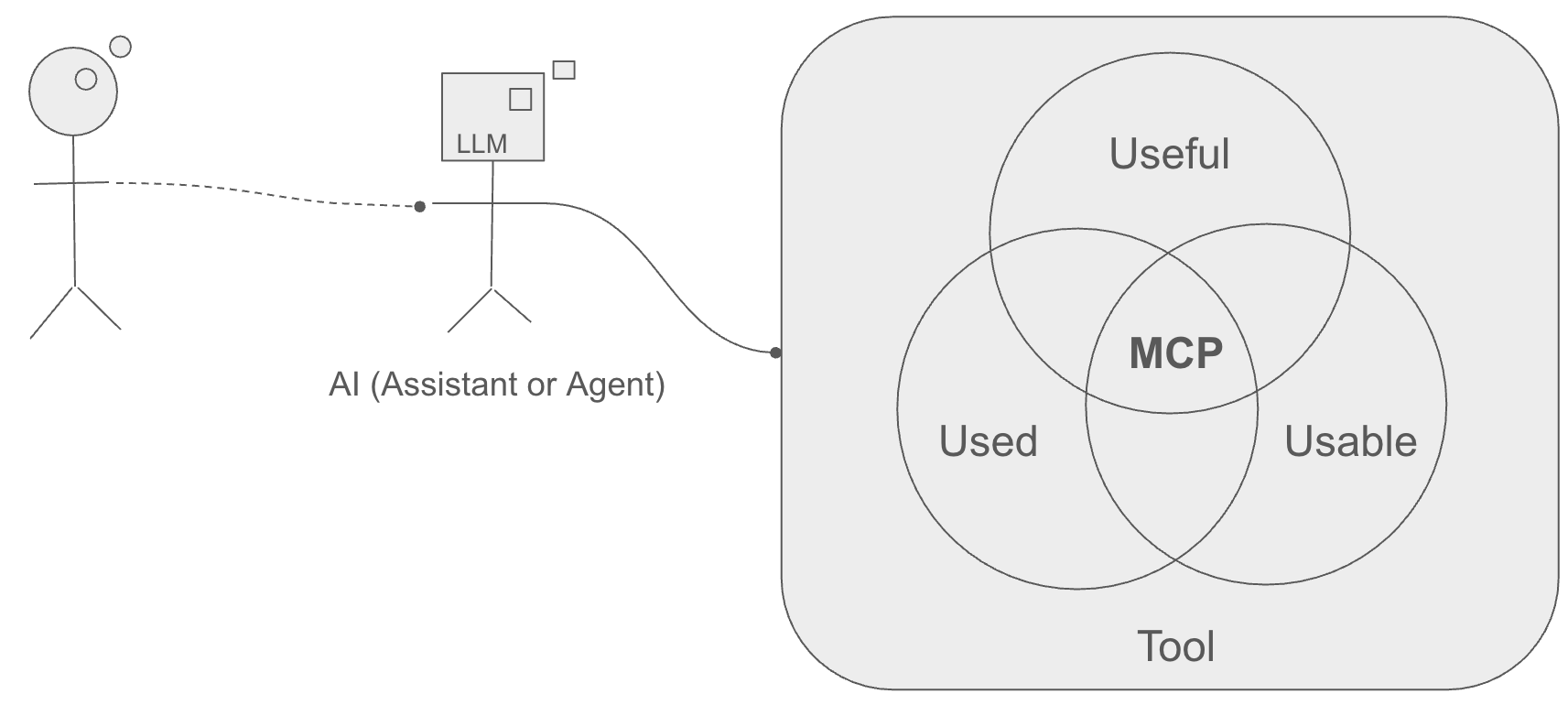

MCP's 3 U's: Making a Tool Useful, Usable, and Used by and for an LLM

Since its announcement a couple of months ago, the Model Context Protocol (MCP) has gained significant attention.

Initially, MCP served as a straightforward mechanism, essentially a plugin system, to grant Large Language Models (LLMs) the ability to interact seamlessly with their environment, thus enhancing AI assistants and agents. Applying Wardley’s theory to trace the protocol’s evolution, I’d argue that MCP has progressed beyond Stage I (labeled genesis in the image), establishing a certainty of solution. Furthermore, its widespread adoption suggests it has entered Phase II (labeled Custom Built on the image).

Note it is beyond the scope of this article to explain Wardley’s theory. See the reference on Simon Wardley’s blog for more info)

Consequently, we’re observing products crafted with MCP. The subsequent phase involves developing products around MCP.

Personally, my focus remains on exploring the protocol to identify the specific problems it can effectively address.

I previously blogged about a Proof of Concept (POC) developed during MCP’s Stage I, a time when confirming the protocol’s viability was paramount.

Currently, I interact with an AI that leverages various tools. My setup features middleware exposing a REST API compatible with OpenAI v1. As a user, I engage through a UI, which communicates with the middleware. The middleware, in turn, invokes the inference engine to provide input to the LLM and orchestrates calls to MCP tools in the order determined by the LLM.

Integrating MCP servers into the middleware is simple, instantly enabling them as capabilities accessible to the LLM.

The MCP protocol, along with its middleware implementation, ensures that any tool becomes usable by any LLM compatible with my inference engine (currently, I utilize Vertex AI from Google, with plans to incorporate support for Ollama in the future.)

This article focuses on understanding how to craft tools that fulfill the 3Us (usable, useful, used) from the perspective of the LLM. In this article, I will explore the notion of prompt exposition of the MCP protocol, showing why it is important to consider when moving from an MCP POC to an MCP product.

{JSON-RPC + NLP}: Organon Organōn (the tool of tools)

MCP provides an answer to the question: “How does the user (the LLM in our case) interact with the tool?” by offering a communication structure: JSON-RPC.

But, in fact, there are two languages involved in this communication, both stemming from the LLM trying to achieve its goal with a tool:

- JSON-RPC, as mentioned, governs tool manipulation.

- Natural Language supports why the user (again, the LLM) should use the tool.

Therefore, it is mandatory to have a clear description of the tool exposed through MCP, similar to proper documentation. LLMs understand our language, so we should provide them with our documentation.

Without this documentation—clear descriptions and illustrative prompts—the tool lacks affordance from the LLM’s perspective. In human-computer interaction, affordance refers to the quality of an object or environment that allows an individual to perform an action. For an LLM interacting via text, affordance means the tool’s textual description (its name, parameters, documentation, and associated prompts) must clearly signal what it does and how to use it correctly. If these textual cues are missing or ambiguous, the LLM cannot easily perceive the tool’s utility or operational requirements, and consequently, the tool may not be used, even if it’s potentially useful.

Useful to ensure it is used

Simply documenting the tool is not the best way to provide affordance from the perspective of an LLM.

To further assist the LLM, the MCP server can expose prompts. When I first encountered prompt exposition in an MCP tool, I questioned its inclusion in the protocol.

Actions and Resources are easily understandable for programmers, like to POST and GET requests in a REST API.

But what about prompts?

According to the standard, MCP prompts enable servers to define reusable, user-controlled prompt templates and workflows.

My understanding is that prompt exposition helps ensure the tool is useful to the LLM.

Beside solving repetitive and complex problems, they simplify the critical task of gathering and injecting relevant context (like specific code files or logs) needed for meaningful results, and they make the server’s specific, high-value LLM capabilities easily discoverable and accessible to the end-user via the client interface. This transforms abstract potential into concrete, readily available actions.

In short, MCP prompts help the LLM (and the user interacting via the LLM or client) to answer those questions:

- Why would someone use this tool: is this useful to solve my target problem?

- But more important: How do I use it effectively? (By selecting the appropriate prompt and providing the required arguments, often simplified by the client UI).

Illustration through a use-case

Anthropic proposes a tool called memory. Memory is a knowledge graph-based system that can be used to share elements between contexts. Think of it as a structureless database that can store relationships between different entities.

For example, you can store: “MCP’s 3 U’s: Making a Tool Useful, Usable, and Used by and for an LLM” “written by” “Olivier”.

- “MCP’s 3 U’s: Making a Tool Useful, Usable, and Used by and for an LLM” and “Olivier” are nodes in the graph.

- “written by” is an edge.

The entity {“MCP’s 3 U’s: Making a Tool Useful, Usable, and Used by and for an LLM” “written by” “Olivier”} is a “triple,” and one way to interact with the knowledge graph is to expose functions like “add_triple” or “get_triple.” The MCP service can then expose a set of resources to fetch elements based on their relationships (e.g., all elements “written by” “Olivier”).

This is very powerful because it is schemaless: you can store anything in a node and any relationship between two nodes.

To represent knowledge, only a small set of functions is needed:

- Creation/Maintenance:

add_tripleandremove_tripleallow you to build and curate the graph. - Retrieval:

find_triplesis a versatile workhorse for retrieving specific facts or patterns. - Exploration:

describe_entityprovides the essential capability to navigate and understand the context around any given node, which is key to discovering insights and relationships in a graph structure.

We can then let the LLM analyze a text and create a structure accordingly. For example, here is what I asked Gemini (regarding the article you are reading):

simulate the creation of a knowledge graph by writing all the calls to a function `add_triple(subject, predicate, object)` you would do to represent this article:

Since its announcement a couple of months ago, the Model Context Protocol (MCP) has gained significant attention.

...Its reply is:

# Core Concepts and Definitions

add_triple("Model Context Protocol", "alias", "MCP")

add_triple("MCP", "description", "A mechanism to grant LLMs the ability to interact seamlessly with their environment")

add_triple("MCP", "type", "Protocol")

add_triple("MCP", "initialPurpose", "Plugin system for LLMs")

add_triple("MCP", "enhances", "AI assistants")

add_triple("MCP", "enhances", "AI agents")

# Evolution and Stages (Wardley's Theory)

add_triple("MCP", "evolutionAnalyzedWith", "Wardley's theory")

add_triple("Stage I", "label", "genesis")

add_triple("MCP", "established", "certainty of solution")

add_triple("MCP", "enteredPhase", "Phase II")

add_triple("Phase II", "label", "Custom Built")

add_triple("MCP", "adoption", "widespread")

add_triple("Products", "areCraftedWith", "MCP") # Implied relationship in Phase II

add_triple("Products", "developedAround", "MCP") # Subsequent phase mentioned

# Author's Interaction and Setup

add_triple("Author", "focusesOn", "exploring MCP")

add_triple("Author", "focusesOn", "identifying problems MCP can address")

add_triple("Author", "bloggedAbout", "POC")

add_triple("POC", "type", "Proof of Concept")

add_triple("POC", "developedDuring", "Stage I")

add_triple("Author", "interactsWith", "AI")

...So far, so good… and it worked. Using the MCP tool actually creates a file with this content that I can then query by asking:

what does MCP enhance according to the graph?

MCP enhances AI assistants and AI agentsSo the tool is Useful… but is it really usable? Take the following line:

add_triple("MCP", "evolutionAnalyzedWith", "Wardley's theory")

If I ask in a new session to update the memory with another article analysis, how can I be sure that it will use “evolutionAnalyzedWith” and not something else?

For example, I asked the same question to the same LLM in another context, and I received this answer:

add_triple("Wardley's theory", "applied_to", "MCP evolution")

This inconsistency is problematic. The LLM, trying to be helpful, invents relationship terms (evolutionAnalyzedWith, applied_to) that seem reasonable in isolation but lead to a fragmented and unreliable knowledge graph over time. Queries become difficult because you don’t know which predicate term was used. The core issue is the lack of a predefined structure or vocabulary for the relationships the LLM is creating. The knowledge graph implementation, while flexible, is not semantically affordant – it doesn’t guide the LLM on how to structure the knowledge consistently.

Ontology, the missing part

This is where an ontology comes in. An ontology acts like a formal schema or a controlled vocabulary for the knowledge graph. It explicitly defines:

- Classes: The types of entities allowed (e.g.,

Protocol,Theory,Person,Article). - Properties (Predicates): The allowed relationships between these classes (e.g., defining a single, specific predicate like

analyzedUsinginstead of allowing variations likeevolutionAnalyzedWithorapplied_to). - Constraints: Potentially, rules about how classes and properties can be combined (e.g., only a

Personcan be the object of awrittenBypredicate originating from anArticle).

By defining which predicates are valid and what types of nodes they can connect, an ontology provides the necessary constraints. It guides the LLM to use standardized terms, ensuring that knowledge added to the graph is consistent and queryable, regardless of the input text or session. It essentially enforces semantic agreement, directly addressing the problem of inconsistent predicate invention."

But what does it have to do with MCP Prompts?

Well, as I would with a colleague, I can explain what I expect and the basics of an ontology to my AI.

For example, I could provide this prompt to my LLM, and it would produce a very similar answer for the text (depending on its ability to analyze the text, but formalizing the output would be the same):

Your task is to analyze the following text and extract relationships according to a specific ontology.

**Ontology Rules:**

1. Identify entities of type 'Person', 'Manager', and 'Team'.

2. Extract relationships *only* if they match these patterns:

* Subject Type: Person, Predicate: 'worksFor', Object Type: Manager

* Subject Type: Person, Predicate: 'isMemberOf', Object Type: Team

* Subject Type: Team, Predicate: 'hasLeader', Object Type: Manager

3. Represent entity names as accurately as possible from the text.

**Action Required:**

For *each* valid relationship you identify that strictly conforms to the ontology rules above, you **must** call the ` + "`InsertTriple`" + ` action.

* Use the identified entity names for ` + "`subject`" + ` and ` + "`object`" + `.

* Use the corresponding predicate ('worksFor', 'isMemberOf', 'hasLeader').

Do not insert triples for relationships or entity types not explicitly mentioned in the ontology rules. Ensure the types of the subject and object match the rule for the predicate used.

Here is the text to analyze:`

...The idea behind the MCP prompt is to encode this text and serve it on demand.

How does it work?

The MCP server exposes a “command” prompt that takes an argument, which is the text to analyze.

The “command” here is called extract-relations-from-text (I only use it as a validation of the concept). Its description is important to make it usable, but let’s keep this for later, as I will encourage my LLM to use it.

Here is a sample implementation with mcp-go, provided as an illustration:

return mcp.NewPrompt("extract-relations-from-text",

mcp.WithPromptDescription("Analyzes text to extract Person-Manager-Team relationships according to a specific ontology and inserts them as triples using InsertTriple."),

mcp.WithArgument("input",

mcp.ArgumentDescription("The text containing information about people, managers, teams, and their relationships."),

mcp.RequiredArgument(),

),When the LLM, running within the Inference Engine, signals its intent to use an MCP prompt (like extract-relations-from-text), the middleware receives this signal. The middleware then fetches the actual prompt text from the MCP tool server. Then, the middleware packages this received prompt text along with the original user data into a new, correctly formatted request and sends it to the Inference Engine. The Inference Engine then processes this request, feeding the injected instructions and data to the LLM. The LLM follows these instructions, and its resulting decisions (like wanting to call inset_triple) are interpreted by the Inference Engine, which sends the structured action requests back to the middleware for execution via the MCP server.

Demo…

I have implemented this MCP server (https://github.com/owulveryck/mcpkg) and am using it with my openaiserver with Big-AGI as a frontend. For the purpose of this demo, I did not write a specific system prompt; instead, I am directly instructing my LLM to use the prompt.

extract Person-Manager-Team relationships from this text:

The fluorescent lights of "Innovate Solutions Inc." hummed, a constant backdrop to the quiet chaos of the Marketing Department. At the helm was Anya Sharma, the Marketing Director, a whirlwind of energy and strategic thinking. Anya reported directly to Mr. Thompson, the CEO, a man whose presence was mostly felt through terse emails and occasional, anxiety-inducing office visits.

Reporting to Anya were two team leads: Ben Carter and Chloe Davis. Ben, a seasoned marketer with a knack for data analysis, led the Analytics and Insights team. His team consisted of two junior analysts: Raj Patel, a recent graduate brimming with enthusiasm, and Sarah Chen, a meticulous researcher with an uncanny ability to spot trends. Ben often found himself mediating between Raj's eagerness to implement every new idea and Sarah's cautious, evidence-based approach.

...I have processed the text and extracted the Person-Manager-Team relationships based on the ontology rules you provided. I have inserted the following triples into the knowledge graph:

* Anya Sharma worksFor Mr. Thompson

* Ben Carter worksFor Anya Sharma

* Chloe Davis worksFor Anya Sharma

* Analytics and Insights team hasLeader Ben Carter

* Raj Patel isMemberOf Analytics and Insights team

...Under the hood, it received the prompt from the MCP server, analyzed it, and called the add_triple actions of the MCP server accordingly. I have a file named my_knowledge with all this information, which I can share across contexts or with another colleague’s assistant.

When this server becomes a proper product, the next features would be to create a proper prompt template that answers different types of ontologies depending on the arguments, perhaps using schema.org as a reference. I will blog about this if this tool evolves according to my needs.

Conclusion: Designing Products for the AI User

Ultimately, an MCP server is more than just code connecting an LLM to a capability; it’s a digital product in its own right. However, it’s a product designed for a unique kind of user: not a human navigating a GUI, but an AI interacting through language and structured calls. This fundamental difference shifts the design paradigm.

For software developers and product owners, understanding ‘affordance’ takes on a new dimension. It’s no longer solely about visual cues or intuitive layouts for humans. Instead, it’s about crafting clear textual descriptions, defining precise functions (Actions/Resources), and, crucially, designing intelligent MCP Prompts. These prompts must effectively communicate what a tool does, why it’s useful for a specific task (its potential application as a solution), and how the AI should use it correctly and consistently, often guided by underlying structures like ontologies.

As the knowledge graph example illustrates, without this carefully designed semantic guidance—making the tool’s purpose and proper usage obvious to the AI—even a technically usable tool can fail to be reliably useful or consistently used.

Recognizing the AI as the end-user and designing for its unique interpretive needs through well-structured MCP interfaces, especially prompts, is therefore critical. It is fundamental to successfully applying these powerful AI capabilities as solutions to real-world problems, as envisioned by the product creators. Only by understanding and acting on this new requirement for AI-centric affordance can developers and product owners ensure their MCP-based tools achieve their full potential and are truly effective components of the AI ecosystem.

Next on my list of things to try: notifications, to truly turn my assistant into an agent, allowing it to react to events.