Exploring exaptations in engineering practices within a RAG-Based application

Context

In this article, I will explore the concept of RAG, but not in the typical way. My aim is to essentially create a RAG from the beginning to view it as a purely engineering problem.

Starting from scratch will enable me to:

- potentially uncover a form of exaptation that can inform my decisions as an engineer and guide me in a specific direction.

- clarify any points of confusion I may have in comprehending the system.

Note: The from scratch approach is difficult because the generation of the embedding is linked to the model and tokenization, but let’s consider it as from scratch for the Engineering part, which will be sufficient for me.

As a bootstrap, I used the information from this article because it’s clear and written in Go, and I am fluent in that language. I have no additional insights to offer beyond the original article on the technical part (the author made a great job).

Therefore, this isn’t an article about Go, but really an article about IT engineering.

In this article, I will write the step by step method I used to write a simple (and non-efficient nor effective) RAG, but I will also note the discoveries that may be useful for my work as a consultant and engineer.

Organisation of the article and of the code

- The initial section discusses data acquisition, emphasizing the significance of preparing the data to be readily utilized by a Language Model (LLM).

- The subsequent section involves transforming the data into a mathematical representation that facilitates easy searching. The outcomes are stored in a database that will be utilized by the application.

- The final section pertains to the application itself: it will interpret a question, identify the relevant data segment in the database, and query the LLM.

- The document concludes with a summary and suggestions on how to convert this Proof of Concept (POC) into a custom-made solution.

The sequence of the program is roughly this:

The use case

In the introductory section, I outlined the anticipated outcome I am aiming for. This result revolves around discovering the partial answers to the question: “What is the engineering role in the setup of an application powered by AI”. To effectively steer my actions towards this goal, I require a use-case. This use-case should have a clearly defined output that signifies the conclusion of this experiment.

Below is the detailed description of the use-case:

I frequently dig into books that I regard as “reference” materials, such as “team topologies,” “DDD,” and others. One such reference that I’m currently engrossed in is “the value flywheel effect”.

This insightful book not only discusses strategy but also offers guidance on how to apply Simon Wardley’s theory. It describes a wide range of use case, such as how to utilize maps in a conversation with a CEO, or how to map out a technological solution.

In the realm of consulting assignments, mapping proves to be an invaluable tool. This book is a treasure trove of crucial information for maximizing the effectiveness of these tools.

As an illustration, I have compiled a list of questions that can function as an interview framework during a consulting mission.

My present goal is to interact in a “conversation” with my virtual assistant, posing particular inquiries and obtaining responses grounded on the book.

To achieve this, I will employ a RAG strategy: Retrieve the content corresponding to my query, Augment the prompt with the information retrieved, and then allow the LLM to Generate the reply.

First Step: Data Acquisition

The initial stage in creating a RAG involves gathering the necessary data and conducting a thorough cleanup.

Data Collection

To experiment with the RAG, I need data, or in this case, a book. For The Value Flywheel Effect, I purchased the book.

However, there’s an initial hurdle to overcome: the need to secure the rights to use the data. Simply owning the book doesn’t grant me the liberty to manipulate its content. This is due to the book’s licensing restrictions that prohibit such actions. For now, to verify the project’s viability, I’ll use a different book.

This alternative book is under a creative commons license, already formatted, and is a work I’m familiar with. Additionally, it’s relevant to the subject matter: it’s Simon Wardley’s book.

First Lesson (obvious): Having access to the data is a significant advantage. I’ve always been aware of this, but this experience truly emphasizes its significance.

Data Cleanup

Simon Wardley’s book has been converted into many formats. This repository provides a version in asciidoc.

The text will be fed into the LLM, which is a Language model. Therefore, it’s crucial to aid the LLM in pinpointing the main component of the text - the content, and eliminate any distractions designed to help the human reader, such as centering or font size. However, we do not wish to remove the structure and segmentation of the text, which serve as important indicators and dividers of the content.

In this scenario, Markdown proves to be exceptionally useful. The syntax is simple enough and consumes few tokens and therefore avoid creating any noise for the system.

A little bit of “asciidoc and pandoc” and there you go: a few markdown content files.

Second lesson: I was lucky because someone had already done the conversion work into a “digitally exploitable” format. This step can be long and is a data engineering task.

Second step: creation of the embedding

This is a part that also falls under engineering. This part will aim to convert pieces of text into numerical representation (an array of numbers, a vector). This process is called embedding (or word embedding).

An algorithm is used for converting a set of token (roughly pieces of words) into vectors. As seen before, this algorithm is linked to the model that we will use. Simply put, the program will call an OpenAI API for each piece that will return the corresponding vector. This vector is then stored in the database.

But how to slice the text ? Shall we slice it into fixed size parts? Shall we slice it by chapters? Paragraphs? It depends! There’s no universal approach. To clarify, let’s take a step back and sketch out the basic concepts.

The workflow I’m going to use is based on a question I’ll pose to my engine. The first step involves understanding the question and, depending on its context, identifying a section of the document that might contain the answer.

The process of embedding translates text into a “vector”. We then use mathematical tools to identify vectors that are similar. These similar vectors are likely to be dealing with the same context. Hence, it’s essential to precisely segment the text into sections to create relevant and meaningful vectors.

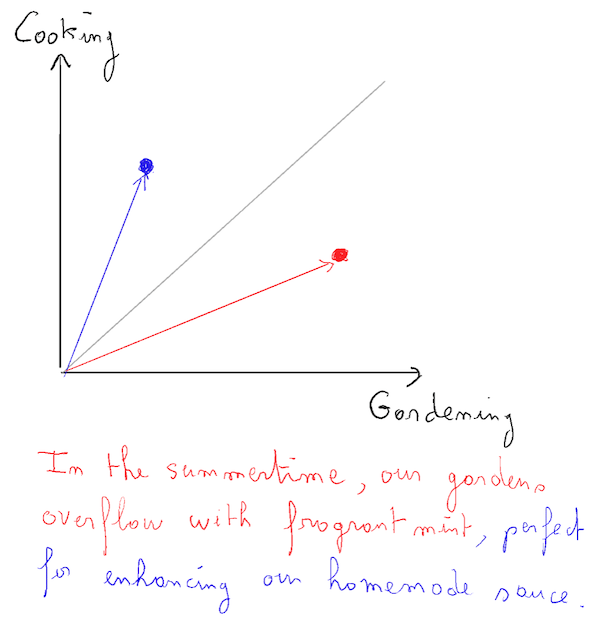

Consider this sentence as an example:

“In the summertime, our gardens overflow with fragrant mint, perfect for enhancing our homemade sauce”.

Let’s say I have a vector representing “cooking” that is vertical, and another vector representing “gardening”. The entire sentence will lean more towards cooking than gardening. However, if I split the sentence into approximately two equal parts, I’ll have one segment that is closely related to gardening, and a non-essential segment, closely related to cooking.

Third lesson (obvious): A “business” expertise may be necessary to analyze the data and achieve maximum efficiency in the application.

For the purpose of this test, I will divide the data into equal segments of x number of words. This might be sufficient for the validation of my Proof of Concept.

I execute the code exactly as outlined in the original blog post. This process will segment the text, invoke the OpenAI embedding API for each segment, and subsequently store the outcome in a relational SQLite database.

Possible exaptation: I ultimately obtain a SQLite database that encapsulates the Wardley book in a mathematical model compatible with OpenAI. If I possess multiple books, I have the option to either expand this database or establish separate databases for each book. The intriguing aspect is that the SQLite database serves as a standalone knowledge base that can be utilized with the OpenAI API. This opens up the possibility of writing any additional code that leverages this database in whatever language seperating the “building process” of the “run process”.

Last step: inference

Inference forms the core of my application. The process begins when I enter a question. The application then scours my database to find the piece that aligns with the context of the question. This information is then forwarded to OpenAI, which generates a response.

In this scenario, there is no vector base, and the search process is straightforward:

- First, we compute the embedding of the question. This is done through an API call, similar to how we calculate the embedding of the pieces.

- Next, we conduct a cosine similarity calculation for each element in the database.

- We then select the best result, which is the one that is most pertinent to the question.

- Finally, we send this result to the LLM engine via API in prompt mode, along with the original question.

Similarity computation: identifying the relevant segment

If the input dataset expands in size (for instance, if I use the same database for multiple books), a more efficient approach for computing similarity will become necessary. This is where the power of a vector database shines.

Currently, the similarity calculation is manually executed in a large loop using a basic similarity calculation algorithm. However, if the volume of data becomes too large (for example, if I aim to index an entire library), this method will prove inefficient. At this point, we will transition to a vector-based approach.

This vector-based system will identify the most suitable “neighbor”. It remains to be seen which algorithms they employ. Do all vector bases yield the same result? This is a fascinating aspect that I believe warrants further exploration in my role as a consultant.

Lesson Four: Avoid over-engineering or complicating your tech stack, specially in the genesis/POC phase. Instead, concentrate on addressing your specific problem. Seek the expertise of specialists when necessary for scaling (when entering stage II of evolution: crafting).

Let’s prompt

The final step involves constructing a prompt using the extracted information, which will then be sent to the LLM. In my specific scenario, this involves making a call to the OpenAI API.

Below is the basic structure of the prompt that is hard-coded into the program.

The %v placeholder will be substituted with the appropriate segment of text and the corresponding question:

Use the below information to answer the subsequent question.

Information:

%v

Question: %vFourth learning: We enter into prompt engineering, I can replace my hardcoded question with something like:

Use the below information to answer the subsequent question and add the origin.

Origin:

chapter %v

Information:

%v

Question: %vTo do this, I then have to complete my initial database by adding for each piece, its source (chapter). This requires a little thought about its use case upstream.

Database and Prompt Coupling

In reality, the database comprises two tables:

chunksembeddings

The chunks table currently has 4 columns:

idpath- the path of the source file (in my casechapter[1-9].md)nchunk- the chunk number in the segmentation (mostly for debugging)content- the content of the chunk

The embedding table contains:

idembeddingin “blob” format

The information of the prompt needs to be coherent with the information of the database (specially in the “chunks” table). In the exploratory space in POC mode, it’s not a problem, but entering the phase II will require a bit of product thinking and conception ahead of the code.

Results, findings, and fun part

By compiling the program, I can query my knowledge base:

❯ ./rag -db=../../data/db/wardley.db -answer "give me examples of inertia" 2>/dev/null

1. Resistance to change in business due to past success and uncertainty in co-evolving practices.

2. Consumer concerns about disruption to past norms, transition to the new, and the agency of the new when adopting cloud computing.

3. Suppliers' inertia to change due to past financial success, internal resistance, and external market expectations.

4. Financial markets' inertia towards stability and past results.

5. Cultural inertia caused by past success in fulfilling a business model.

6. Resistance to change caused by cutting costs in response to declining revenue in a changing industry.

7. Inertia in reacting to disruptive changes in the market, such as the shift from products to utility services in computing.

8. Inertia in transitioning from custom-built solutions to product offerings.

9. Resistance to change in response to disruptive changes in various industries, leading to companies' demise.

10. Failure to adapt to predictable disruptions, such as the shift from products to utility services, leading to companies' downfall.As the engine is the GPT-x language, I can even ask it in french, it will manage:

❯ ./rag -db=../../data/db/wardley.db -answer "donne moi tous les exemples d'inertie" 2>/dev/null

Les exemples d'inertie mentionnés dans le texte sont :

- "Perte de capital social" : résistance au changement due à des relations commerciales existantes avec des fournisseurs.

- "Peur, incertitude et doute" : tentative des fournisseurs de convaincre les équipes internes de ne pas adopter les nouveaux changements.

- "Perte de capital politique" : résistance au changement due à un manque de confiance envers la direction.

- "Barrières à l'entrée" : peur que le changement permette l'entrée de nouveaux concurrents.

- "Coût de l'acquisition de nouvelles compétences" : coût croissant de l'acquisition de nouvelles compétences en raison d'une demande accrue.

- "Adaptabilité" : préoccupations quant à la préparation du marché ou des clients au changement.Fifth learning: it is observed here that the results are less complete. It is a help, but not a search engine. Idempotence stops at the moment of retrieving information from the embedding base. Then it’s YOLO :D

Conclusion and opening about coupling and software architecture

I have successfully created two independent assets:

- A Go-based binary that doesn’t require installation. It’s designed to query any knowledge base in its specific format.

- The knowledge base itself:

wardley.db

In the future, I can work on a different book, generate an embedding, and share it. The more I break it down into parts, the more valuable the base will become, regardless of the inference engine used.

Key takeaway: The versioning of the program is only loosely tied to my data. This allows me to clean and feed data independently of IT engineering. I might even be able to automate this process through a pipeline.

However, there’s a risk to consider: altering the database could potentially break the SQL queries, and the same applies if I change the prompt.

To mitigate this, I have two options:

- I could version my database concurrently with the code. This means that version 1 of the code would only be compatible with version 1 of the database.

- Alternatively, I could extract the template to create an abstraction. This would result in a strong coupling between the template and the database, but a weaker coupling between the code and the database. (And of course, if I change the database, I’ll have another issue to deal with, but we can manage that with adapters).

A clever approach to managing this coupling is to treat the prompt as a separate asset. This would create a sort of port-and-adapters architecture where communication is conducted by natural language. Fun!