After the BYOD, BYOC (bringing your own cloud): a journey from Home to the World

Context

In the era of work-from-home, I developed goMarkableStream, a tool designed to seamlessly stream content from my reMarkable tablet during video calls. The goal was to replace the physical whiteboard doodling when doing remote meetings.

The tool moved from a proof of concept to become a part of my daily toolbox. The idea behind the tool is:

A service is running on the reMarkable device and captures the image. It exposes a service that serves the image over HTTP(s) with a custom implementation. Then, a renderer is encoded in the browser in WebGL/JS to display the content of the screen. During a video call, I can share a browser tab and therefore share what I am writing with the audience.

Indeed, the solution brought value for remote collaboration and sharing ideas in real-time.

I’ve shared the details of this journey, highlighting how little by little, it bridged the gap between physical and virtual meetings.

However, as the full-time remote work phase has declined and we’ve transitioned back to a more mobile lifestyle, the solution that exposes a service on a local network reaches its limits.

Problem

With hybrid work, and even with a work-from-anywhere situation (home, office, client sites), I faced situations where I tethered my mobile connection to my tablet and was simply unable to stream the content due to limitations.

Therefore, I need a paradigm shift: the service should move from an internal tool, to a service I need to access from anywhere. Streaming over the internet is the way to go.

As I cannot simply expose the streaming service hosted on my tablet to the Internet for obisous reasons, I need to rely on a third party handle the connexion to the outside to the tablet.

This article describes the journey to achieve this, from a simple reverse proxy via NGrok to a VPN solution based on WireGuard.

I will first expose the solution based on a reverse proxy powered by NGrok. The I will explain the limitations that lead me to the solution of accessing the service through a VPN powered by Tailscale. This part will give hints about the wireguard mechanism, and expose the basic elements of the infrastructure in place to expose the streaming service.

Before the pandemic, we used VPNs to connect to the office from home… Now, I’ve switched the paradigm to connect to home from the office. I guess that this is the follow-up of the bring your own device (BYOD) evolution.

First solution: NGrok

As I blogged a couple of months ago, I am using my tablet as support for presentations. This is working smoothly on my own network, but I was facing problems when I moved to a site with limitations. I thought that I could always bring my own laptop with me, but that is not always the case. So, I needed a way to expose the streaming service to the Internet and give the address to the people in charge of presenting the content.

The first and easy step I found as a solution was to embed the NGrok service in my tool. Actually, NGrok’s promise is:

Connect to external networks in a consistent, secure, and repeatable manner without requiring any changes to network configurations.

- Bring Your Own Cloud (BYOC) Connectivity

- IoT Connectivity

The implementation was fairly easy to be embedded in the tool.

Note: I am embedding this in the tool because I want the application to be self sufficient, be less intrusive in the native system of the tablet, and therefore easy to install and run.

Actually, as there is a Go SDK for NGrok and my tool is written in Go, I simply to import and initiate the service.

Basically, NGrok implements a Listener, and all I need to do is to switch the basic listener of the HTTP service to use this listener instead. The magic happens under the hood (connexion to the NGrok service and so on.).

Here is a helper function to initialize the listener based on a configuration structure:

func setupListener(ctx context.Context, c *configuration) (net.Listener, error) {

switch c.BindAddr {

case "ngrok":

l, err := ngrok.Listen(ctx,

config.HTTPEndpoint(),

ngrok.WithAuthtokenFromEnv(),

)

c.BindAddr = l.Addr().String()

c.TLS = false

return l, err

default:

return net.Listen("tcp", c.BindAddr)

}

}And here is its usage in the main loop (handler had been configured before):

l, err := setupListener(context.Background(), &c)

// ...

log.Fatal(http.Serve(l, handler))When I launch the tool, with the correct environment variables, it connects to the NGrok service and displays the external URL to connect to. And voilà: it works!

However, there are constraints and limitations:

- First of all, with the free version of NGrok, the network is limited. I will not be able to use my tool the entire month, but I could live with it.

- The second problem is that I cannot configure the DNS of the endpoint on the free version. And every time it restarts, the URL of the endpoint changes. This is annoying.

All of these problems would have been fixed by paying for the NGrok service, but it is far too expensive for my needs and indeed, would not have solved the last problem:

But the biggest problem is that the solution does not handle roaming (changing networks) and long pauses (when the tablet is sleeping for a long time) well. That made the solution unreliable.

So I looked for another solution.

Next solution: a VPN ?

A potential solution involves making the service accessible over the internet using a consistent name. However, several challenges arise:

- Devices often connect to a private network and access the internet via a gateway.

- Directly exposing the service to the internet poses security risks.

A solution to my problem involves a gateway that directs external traffic to the specified service on my device within the private network. But,tTo accommodate roaming, the gateway must either:

- Be “intelligent” and track the device’s address, or

- Ensure the device’s address within the network remains static.

An intelligent gateway creates a strong dependency on the service and requires a persistence layer to monitor the device’s location, an approach I prefer to avoid.

Alternatively, leveraging the infrastructure to assign a static address to the device is easily achievable by establishing a VPN. This VPN will extend the private network over the internet, keeping the device’s IP address constant, regardless of the connection topology.

In conventional VPN protocols like IPsec or OpenVPN, the VPN’s connection typically depends on the connecting device’s IP address. If the device’s IP address change (e.g., when switching between networks), a typical VPN connection would drop, necessitating the re-establishment of the connection under the new IP address. This procedure can cause delays and disruptions in connectivity.

Fortunately, a modern alternative to traditional VPNs exists: Wireguard!

WireGuard’s Approach

WireGuard, takes a different approach than traditional VPN that inherently supports seamless roaming:

- Connection Identification: WireGuard identifies connections not by the source or destination IP addresses but through the cryptographic identity of the peers (i.e., their public keys). This means that as long as the cryptographic identity remains the same, WireGuard does not care if the actual IP address of a device changes.

- Session Persistence: When a WireGuard client moves to a different network and obtains a new IP address, it simply sends authenticated packets from its new IP to the WireGuard server (or peer). The server recognizes the client by its public key and continues the session without interruption. The server then automatically updates its internal routing table with the client’s new IP address, maintaining the encrypted tunnel without needing to re-establish the connection.

- Rapid Response: This mechanism allows for almost instantaneous switching between networks. Users typically do not notice any disruption in their VPN connection as they move across different networks, making WireGuard particularly suited for mobile devices that frequently change network environments.

WireGuard is fully implemented in Tailscale.

Tailscale implements a software-defined network (SDN). At its core, it establishes a virtual network device at the operating system’s kernel level, thereby providing a network service accessible to all applications.

Challenges and Solutions in Integration

Tailscale is developed in Go, taking advantage of the language’s support for self-contained applications. This approach means that a single binary can encompass all of Tailscale’s functionalities. The Turing completeness of Go facilitates the ease of cross-compilation and porting the code across different architectures.

You simply run ./tailscale and handles the process and create or join an IP network called “tailnet”

Consequently, there is a version of Tailscale compatible with the reMarkable device, which is a Linux-based system operating on an ARM v7 processor.

Sadly, the reMarkable linux kernel does not support the tun/tap device driver, and so it is impossible to run tailscale out-of-the-box.

Note: it was pointed out on Reddit that running Tailscale on the reMarkable is actually possible, as explained here.

However, as Tailscale operates as an SDN, there is an alternative method to connect to the service without depending on kernel support, purely in userspace: tsnet.

Introduction to the tsnet Library

tsnet is a library that lets you embed Tailscale inside of a Go program. This uses a userspace TCP/IP networking stack and makes direct connections to your nodes over your tailnet just like any other machine on your tailnet would. When combined with other features of Tailscale, this lets you create new and interesting ways to use computers that you would have never thought about before.

Implementation of the solution

Like NGrok, tsnet implements a listener, enabling us to modify the function we’ve previously defined to accommodate the “tailscale” scenario.

There’s a neat trick involved. During the first connection, to register the service on the tailnet, the framework displays a URL for authentication via Single Sign-On (SSO). If we turn off the logging, this crucial information no longer appears. While there are several ways to manage this situation, the simplest solution is to initiate the service in “development mode” for the first use (by enabling a specific flag), and then suppress the logging when this flag is deactivated (for instance, when starting as a service).

Here is the proposed implementation:

func setupListener(ctx context.Context, c *configuration) (net.Listener, error) {

switch c.BindAddr {

case "tailscale":

srv := new(tsnet.Server)

srv.Hostname = "gomarkablestream"

// Disable logs when not in devmode

if !c.DevMode {

srv.Logf = func(string, ...any) {}

}

return srv.Listen("tcp", ":2001")

case "ngrok":

l, err := ngrok.Listen(ctx,

config.HTTPEndpoint(),

ngrok.WithAuthtokenFromEnv(),

)

c.BindAddr = l.Addr().String()

c.TLS = false

return l, err

default:

return net.Listen("tcp", s.BindAddr)

}

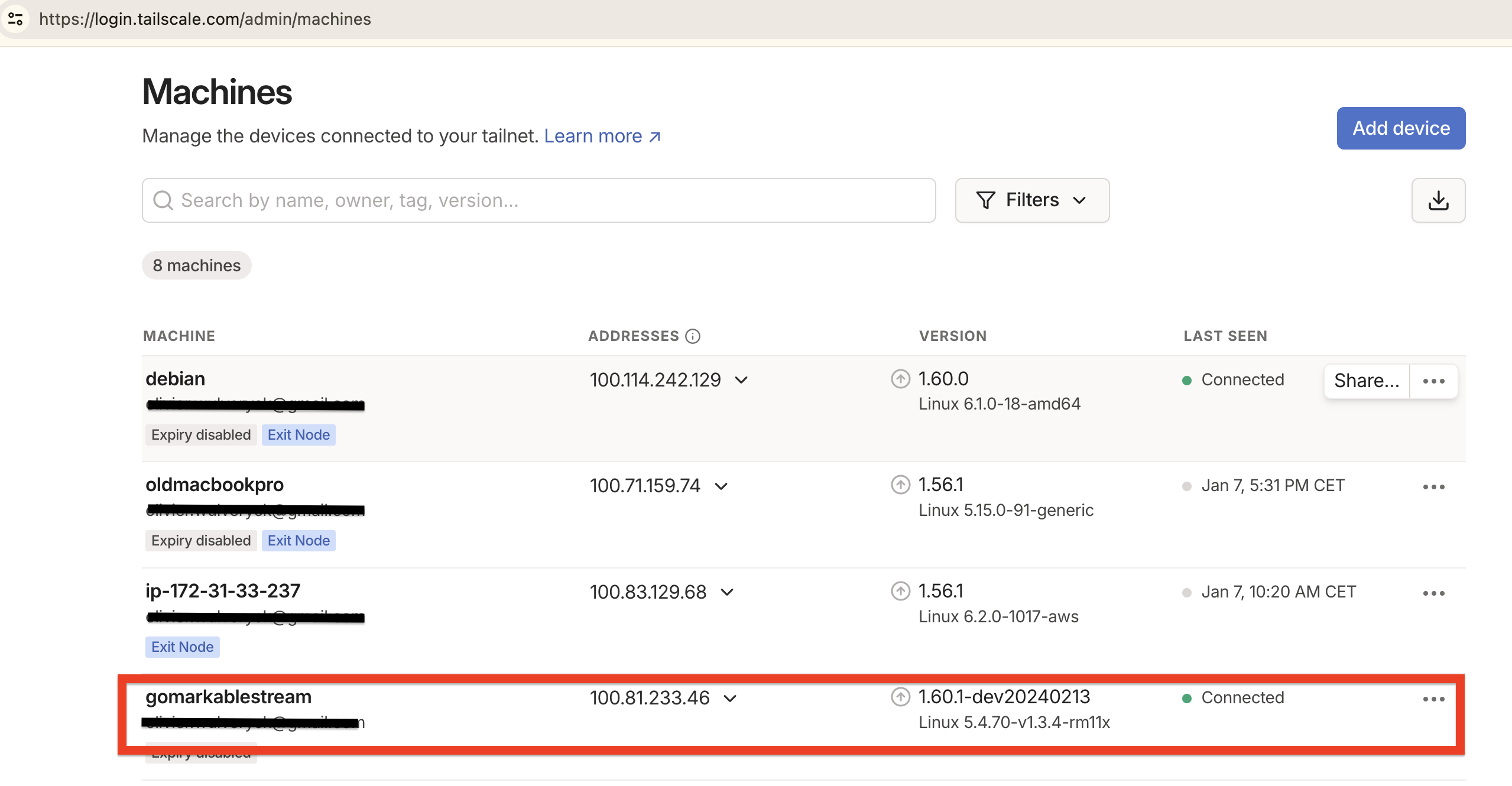

}When the service starts, it exposes the service, and appears on the tailscale console:

The service is then accessible through an http call to 100.81.233.46 (in the example).

The rest of the infrastructure

Now the service is exposed in the VPN, I need to setup a gateway to access it from another network and eventually from the Internet.

I will use Caddy as a reverse proxy on a node of my tailnet. This node will have both a connection the tailnet and a connection to the target network (the one where I need to get the stream).

Caddy as a reverse proxy

The Caddy service will run on an EC2 instance on the internet, with Tailscale installed to ensure the machine joins my tailnet. I will then assign a DNS name to the EC2 instance (for this example, let’s use myremarkable.chezmoi.com).

This example Caddy configuration (Caddyfile) will start the service, automatically obtain a certificate from Let’s Encrypt, and set up basic authentication. Once authenticated, it will route the traffic to the remarkable device.

{

admin off

}

// This is the external name of the node

myremarkable.chezmoi.com {

reverse_proxy gomarkablestream:2001

# Basic authentication

basicauth /* {

user $#ENCRYPTEDPASSWORD

}

}This configuration ensures that accessing https://myremarkable.chezmoi.com from anywhere on the internet will securely display the content from my tablet, provided the tablet is connected to the internet. The service accommodates roaming; thus, wherever I am, I can connect my tablet to the internet (e.g., via my phone) and simply access the URL to seamlessly connect.

Conclusion

This solution is functional but can be enhanced in multiple dimensions.

Firstly, operating a machine continuously in the cloud is neither cost-effective nor environmentally friendly. A more efficient alternative would be to adopt a serverless approach, encapsulating the gateway within a Docker container that is launched “on demand”.

Regarding security, the current approach involves trusting devices within the tailnet. A preferable strategy would involve transitioning to a zero trust architecture, which does not inherently trust any entity inside or outside the network.

I plan to consult my colleague François for assistance in moving towards this direction.

Feature-wise, there’s an interest in upgrading the gateway’s “basic auth” to a more robust mechanism and introducing the capability to generate temporary access. This would allow granting permission to third parties to temporarily view the stream.

Final word

As always, I find joy in confronting the new constraints presented by our evolving world. These challenges not only pose issues but also compel me to embrace my role as an engineer: to identify and execute solutions. This process represents the pinnacle of learning.